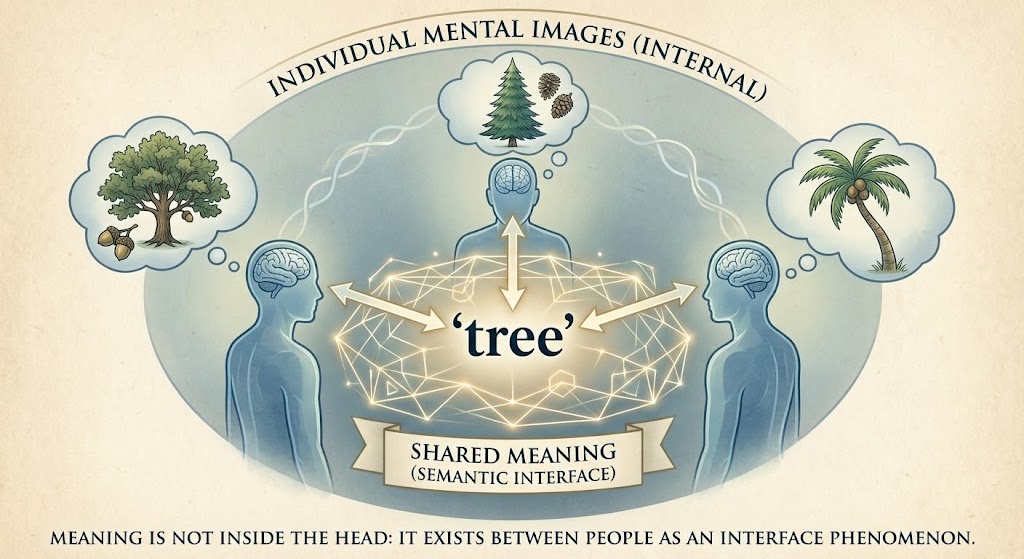

Meaning Is Not Inside the Head

Meaning is often treated as something internal, an idea, a mental image, a representation stored in the brain. But meaning does not reside in individuals. It resides between them. Meaning is an interface phenomenon. It exists in the constraints that coordinate how people interpret and use symbols.

As shown above, this demonstrates how meaning exists between people, not inside their heads. The shared meaning is maintained by the interface, the constraints of language, context, and social norms that coordinate interpretation. When two people communicate, meaning doesn't transfer from one brain to another. Instead, the semantic interface creates the conditions under which both can arrive at compatible interpretations. Meaning is not stored in brains; it is maintained by the interfaces that enable coordination.

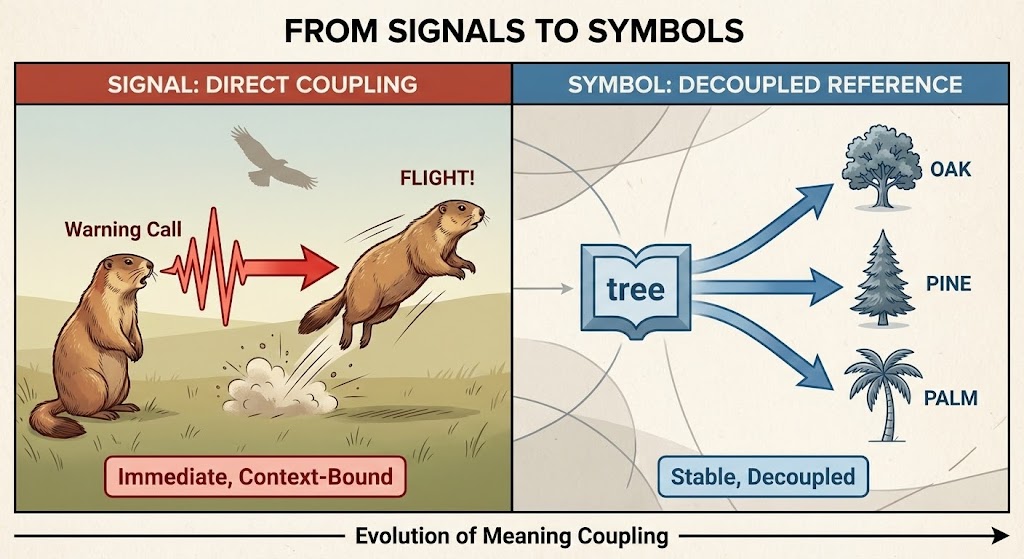

From Signals to Symbols

Not all signals are symbols. A warning call emitted by an animal can trigger flight in others without carrying symbolic content. It directly couples perception to action. Symbolic meaning emerges only when signals become decoupled from immediate responses and instead refer to something beyond themselves.

As shown above, this shows the crucial transition from signals to symbols. Signals directly couple perception to action, a warning call triggers immediate flight. Symbols are decoupled, they refer to something beyond themselves and can be used flexibly across contexts. This decoupling requires stability: a symbol must remain recognizable and meaningful even when the immediate context changes. The semantic interface creates this stability, constraining interpretation enough to support coordination while remaining flexible enough to adapt to new contexts.

This decoupling requires stability. A symbol must remain recognizable across contexts. Its interpretation must be constrained enough to support coordination, yet flexible enough to adapt. That balance is achieved through semantic interfaces.

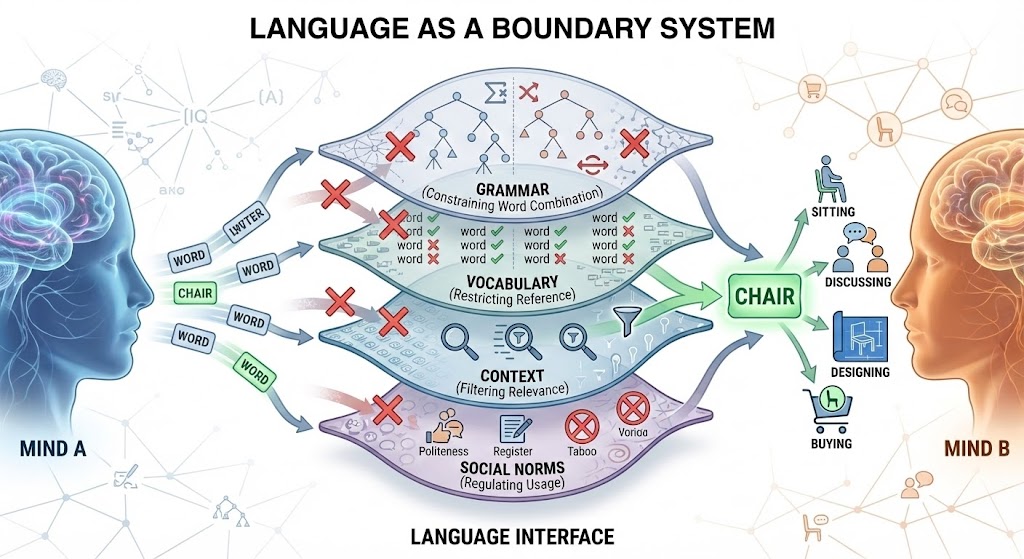

Language as a Boundary System

Language is not just a mapping. It is a regulatory interface that governs how meaning flows between minds. Grammar constrains interpretation. Vocabulary restricts reference. Context filters relevance. Social norms regulate usage.

As shown above, this shows language as a boundary system that regulates meaning flow. Language doesn't just map words to things, it creates the boundaries that make shared meaning possible. Grammar constrains how words can combine, vocabulary restricts what can be referred to, and context filters what's relevant. These boundaries don't limit communication; they enable it by creating the constraints that coordinate interpretation across different minds.

As shown above, this emphasizes that semantics works through constraints, not descriptions. Language doesn't mirror reality, it creates boundaries that make shared reality possible. Grammar doesn't describe how the world is structured; it constrains how words can combine to create meaning. These constraints are the interface, they don't limit what can be said, but enable coordination by creating the structure within which meaning can flow.

Language is not a mirror of reality. It is a boundary that makes shared reality possible. Grammar does not describe the world; it constrains how words can combine to create meaning.

Ontologies as Semantic Interfaces

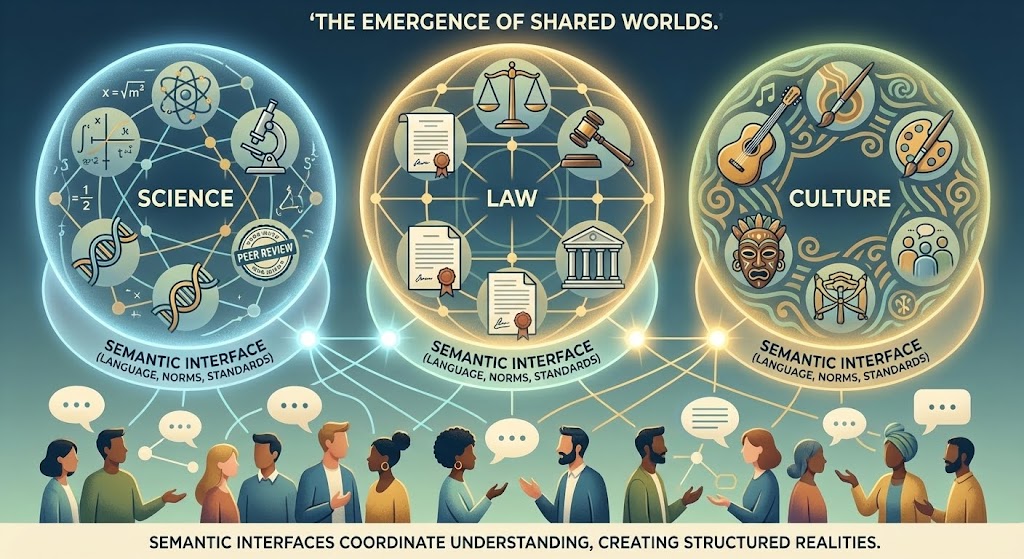

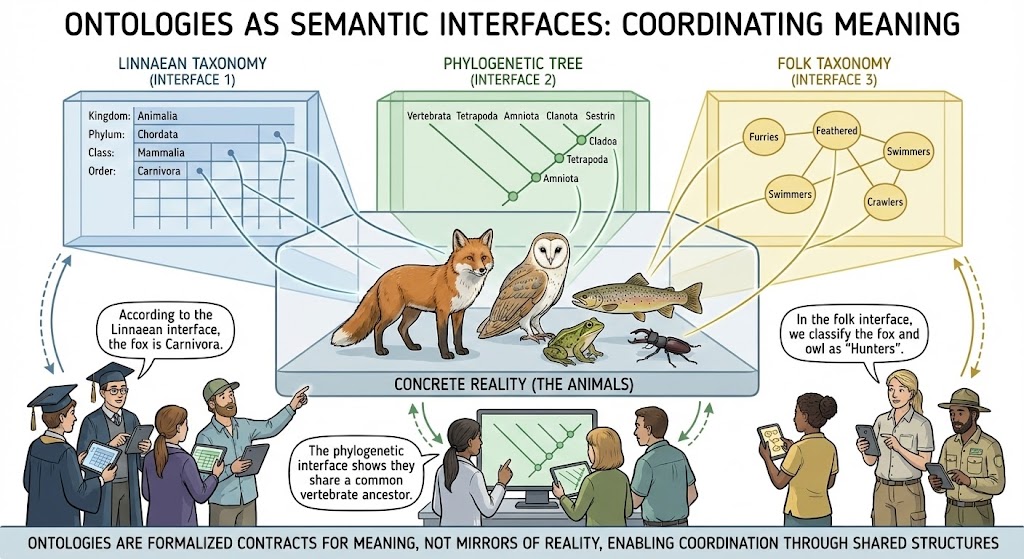

When shared worlds become formalized, when the semantic interfaces are made explicit and systematic, we arrive at ontologies. An ontology is not a catalog of everything that exists. It is an interface that regulates how concepts relate, how statements can be made, and how inferences can be drawn.

As shown above, this shows how shared worlds emerge from semantic interfaces. When people coordinate their interpretations through language, they create shared worlds, realities that exist between them, not just in their individual minds. These shared worlds enable cooperation, knowledge, and culture. The interface here is the semantic constraints that make this coordination possible, creating the conditions under which multiple minds can participate in the same world.

As shown above, this shows ontologies as semantic interfaces, formalized contracts for meaning. An ontology doesn't catalog everything that exists; it regulates how concepts relate, how statements can be made, and how inferences can be drawn. It's a contract that specifies what concepts mean, how they relate, and how they can be used. The ontology creates the interface that coordinates interpretation, enabling different systems to share meaning by respecting the same constraints.

Seen this way, ontologies are not descriptions of the world. They are contracts for meaning. They specify what concepts mean, how they relate, and how they can be used. They create the interfaces that coordinate interpretation.

Key Concepts

- Shared Meaning: Meaning that exists between people, not inside heads

- Symbols: Decoupled signals that refer beyond themselves

- Language: Regulatory interface that governs meaning flow

- Ontologies: Formalized contracts for meaning

- Semantic Constraints: Boundaries that make meaning possible

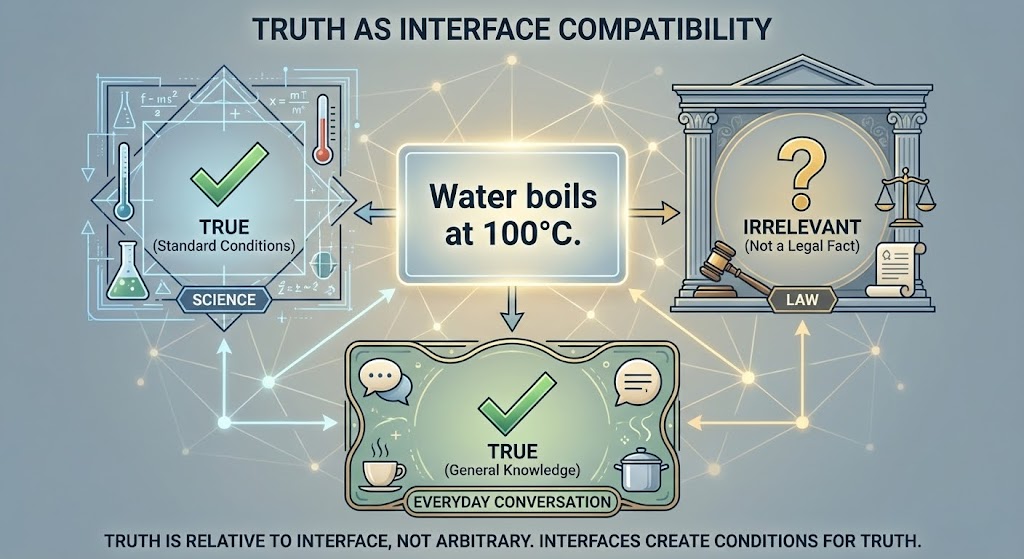

- Truth as Interface Compatibility: Truth relative to semantic interfaces

Building on Cognitive Interfaces

Semantic interfaces build upon cognitive interfaces. They rely on the inferential processes established at the cognitive level, but add the ability to stabilize meaning across systems, enabling communication, knowledge, and culture. This creates the conditions for shared worlds and collective understanding.

As shown above, this shows truth as interface compatibility rather than correspondence to reality. A statement is true relative to a semantic interface if it's compatible with the constraints of that interface. Different interfaces can have different truths, and truth is maintained by the interface itself, not by matching an external reality. This view shows how truth emerges from the coordination enabled by semantic interfaces, creating the conditions for shared knowledge and understanding.

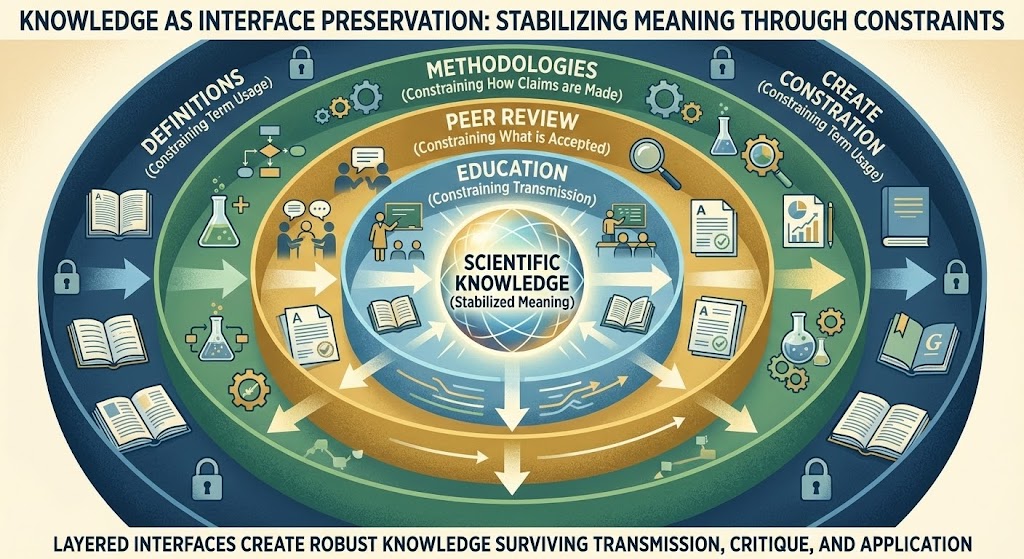

As shown above, this shows knowledge as interface preservation. Knowledge isn't stored information, but the maintenance of semantic interfaces that enable coordination. When we preserve knowledge, we're not just storing facts, we're maintaining the interfaces that make those facts meaningful and usable. Knowledge persists through the preservation of the semantic constraints that coordinate interpretation, enabling it to be shared and built upon across time and space.

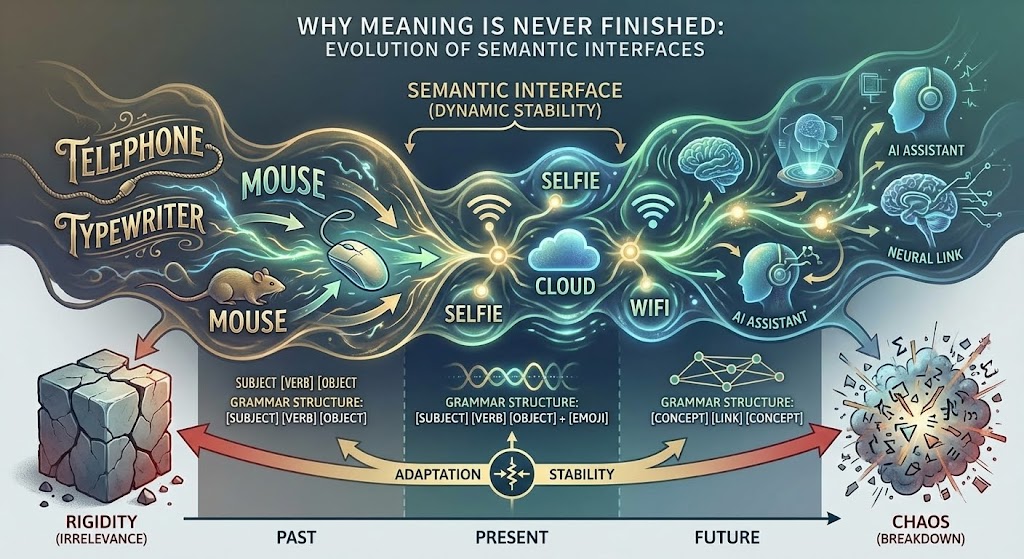

As shown above, this demonstrates meaning continuity, how meaning can persist and evolve while maintaining coherence. Meaning doesn't need to be fixed to be stable. The semantic interface creates continuity by constraining how meaning can change, ensuring that evolution remains compatible with existing interpretations. This allows meaning to adapt and grow while maintaining the coordination that makes communication possible.