Entropy Is Not the Enemy

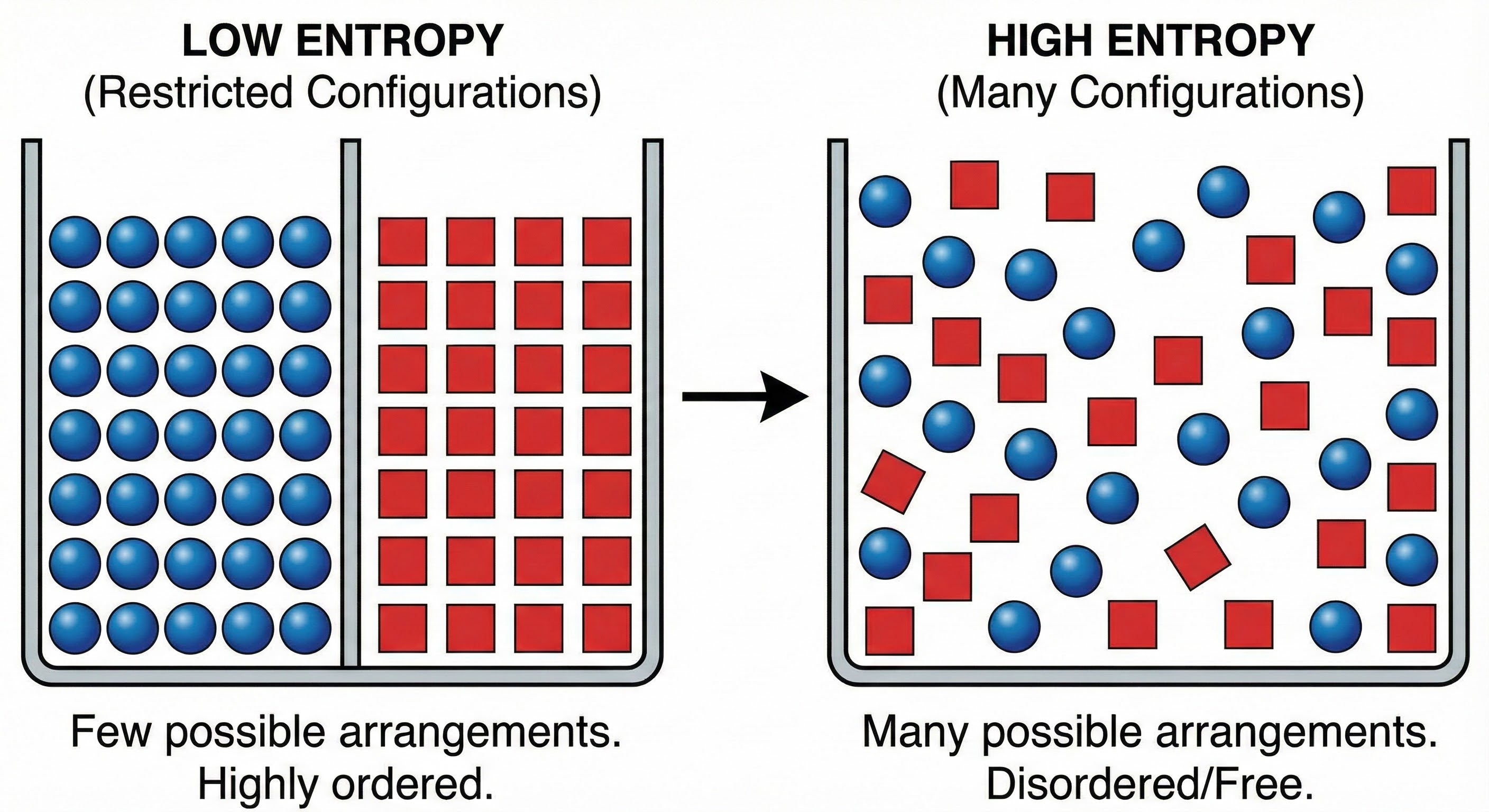

Entropy is often portrayed as the villain of the universe, a force that destroys all structure. This framing is misleading. Entropy is not a force; it is a measure of configuration. High entropy does not mean chaos; it means freedom. Low entropy means restriction.

As shown above, this contrasts low and high entropy states, showing that entropy is fundamentally about the number of possible configurations, not about disorder. Low entropy represents a constrained, organized state with fewer possibilities, while high entropy represents a state with many more possible arrangements. The key insight is that order can be maintained locally even as entropy increases globally, through interfaces that manage the flow.

The real question is not why entropy increases globally (that is unavoidable), but how local reductions in entropy are sustained long enough to matter. How does a cell maintain its internal order while the universe around it becomes more disordered? The answer is always the same: through interfaces that allow entropy to be exported.

As shown above, the entropy pump concept shows how systems can maintain local order by exporting disorder. Like a pump that moves water, thermodynamic interfaces move entropy from inside the system to the outside environment. This illustration demonstrates the mechanism by which living systems maintain their structure: they don't violate the second law of thermodynamics, but rather use interfaces to channel entropy flow, keeping internal order while increasing external disorder.

The Hidden Role of Boundaries

Consider a refrigerator. Inside the fridge, temperature is low and stable. The food maintains its structure. Outside, heat is expelled into the kitchen. The refrigerator does not violate thermodynamics; it relies on a carefully engineered interface, the compressor and coils, that channels energy flow. It creates a boundary that allows entropy to flow out while keeping order inside.

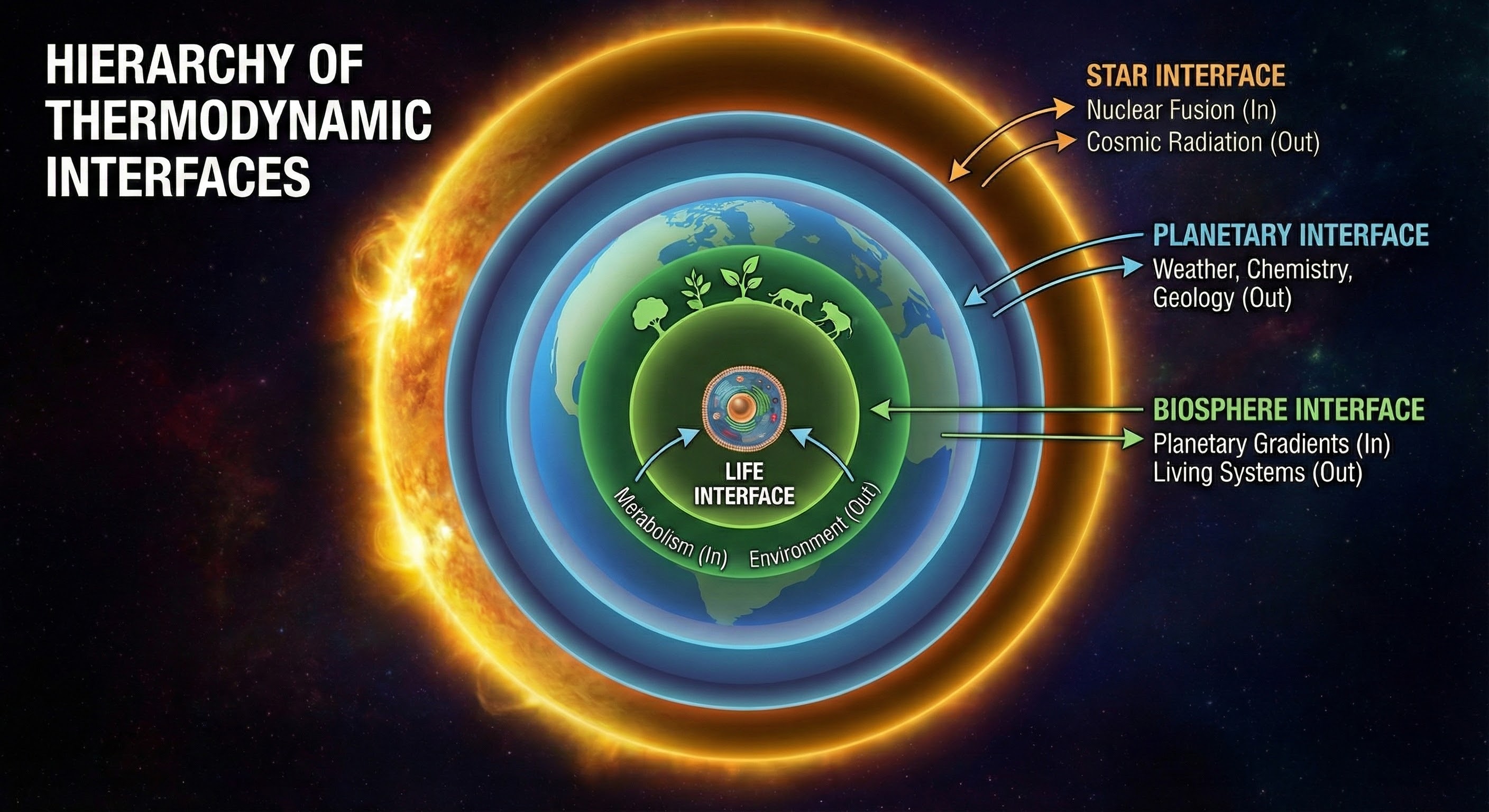

This principle applies everywhere. A star maintains its structure by exporting entropy through radiation. A cell maintains its order by exporting entropy through metabolic processes. A living organism maintains its organization by constantly exchanging matter and energy with its environment.

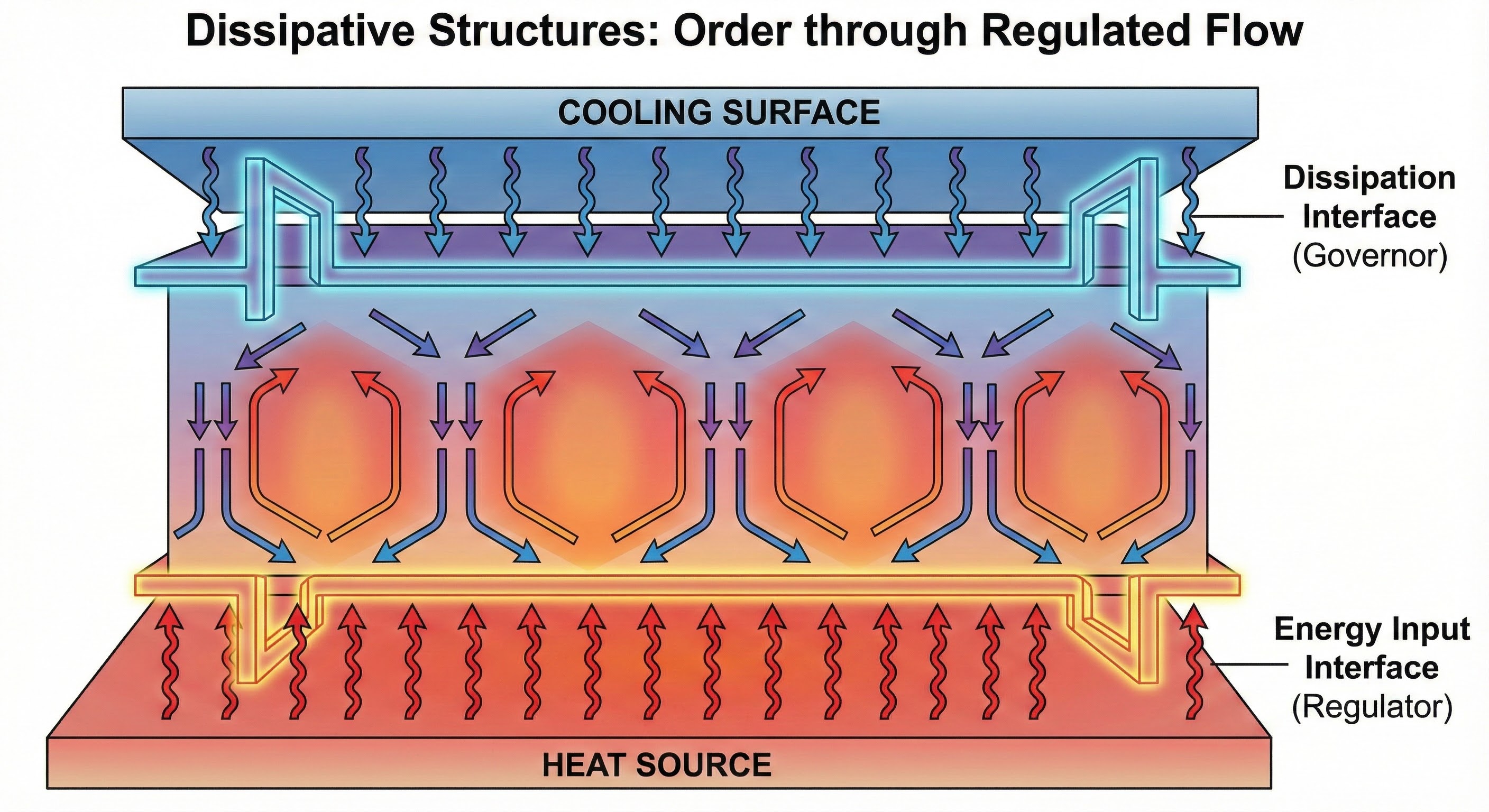

Dissipative Structures

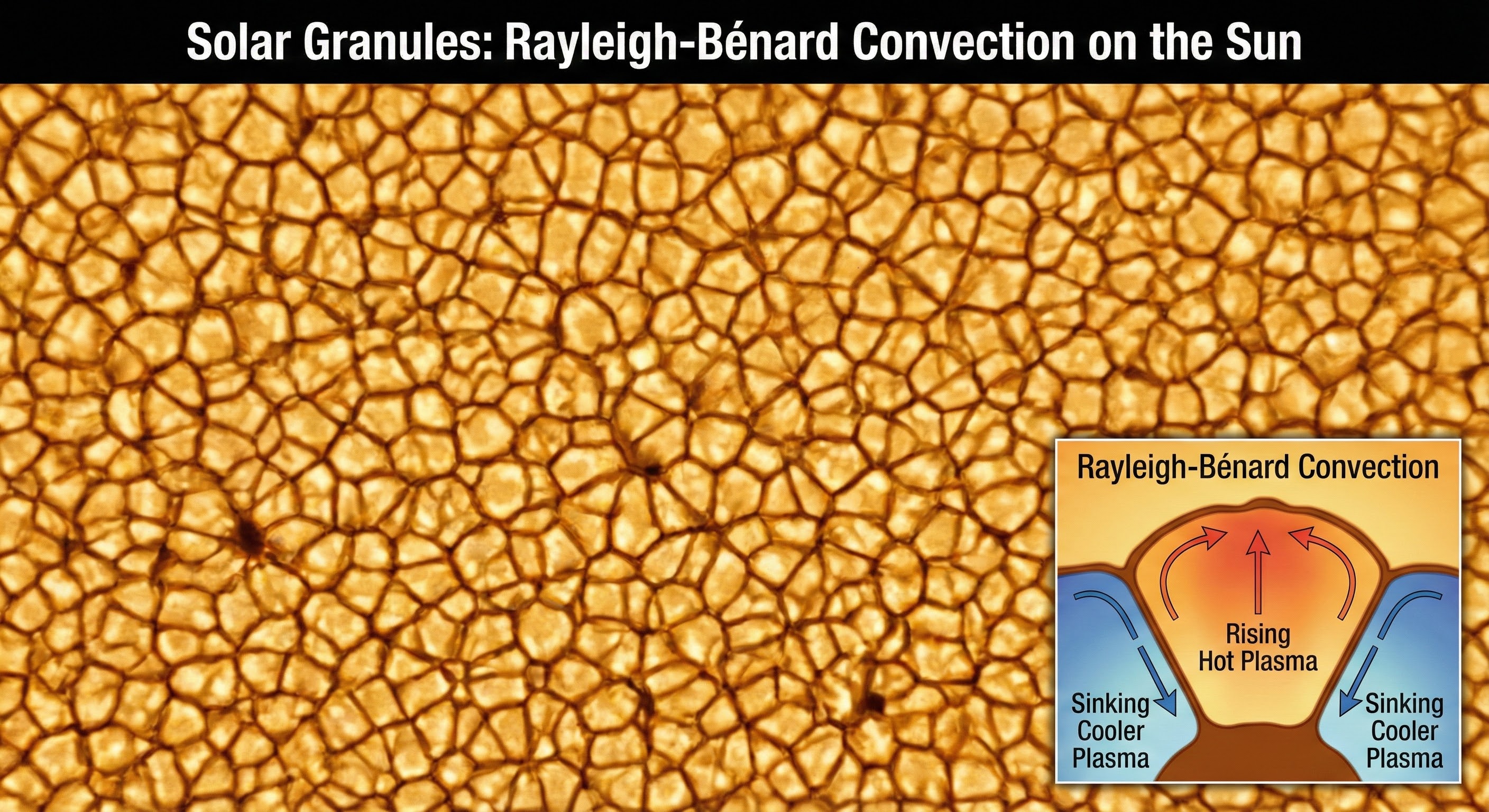

Far from equilibrium, systems can maintain stable patterns by continuously dissipating energy. These are called dissipative structures. They exist in the narrow region between too much order (rigidity) and too much disorder (chaos).

As shown above, solar granules are a perfect example of dissipative structures in nature. These convection cells on the sun's surface maintain their hexagonal pattern by continuously dissipating heat. The pattern is stable not because it's frozen in place, but because it's actively maintained through the flow of energy. The interface here is the boundary between hot rising plasma and cooler descending plasma, creating a self-organizing structure that persists far from equilibrium.

As shown above, this illustrates the general principle of dissipative structures: they maintain order through continuous energy flow. The structure exists in a dynamic balance, where the rate of energy input equals the rate of dissipation. This creates a stable pattern that would collapse if the energy flow stopped, demonstrating how interfaces can maintain structure through flow rather than stasis.

Examples include convection cells in heated fluids, chemical oscillations like the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction, and even living cells. All of these maintain their structure not despite entropy, but by channeling it through carefully designed interfaces.

As shown above, the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction creates stunning spiral and wave patterns that persist as long as the chemical reaction continues. These patterns are not static, they continuously regenerate themselves through the reaction dynamics. The interface here is the chemical reaction itself, which maintains the pattern by continuously converting reactants to products, creating a visual demonstration of how order can emerge and persist through thermodynamic interfaces.

Key Concepts

- Entropy Management: Interfaces that allow entropy to be exported while maintaining local order

- Dissipative Structures: Stable patterns maintained far from equilibrium

- Energy Gradients: Differences that drive flow and create structure

- Far-from-Equilibrium Systems: Systems that maintain order through continuous exchange

- Thermodynamic Boundaries: Interfaces that channel energy flow

- Self-Organization: Emergence of order through thermodynamic interfaces

Building on Physical Interfaces

Thermodynamic interfaces build upon physical interfaces. They rely on the conservation laws and symmetries established at the physical level, but add a new dimension: the management of entropy flow. This creates the conditions under which complex structures can emerge and persist, setting the stage for biological interfaces.

As shown above, this shows how thermodynamic interfaces stack upon physical ones, adding the crucial dimension of entropy management. While physical interfaces establish the fundamental constraints, thermodynamic interfaces enable the emergence of complex, far-from-equilibrium structures. The stacking is not just hierarchical, each layer enables new possibilities that weren't available at the lower levels, creating the conditions for life itself.

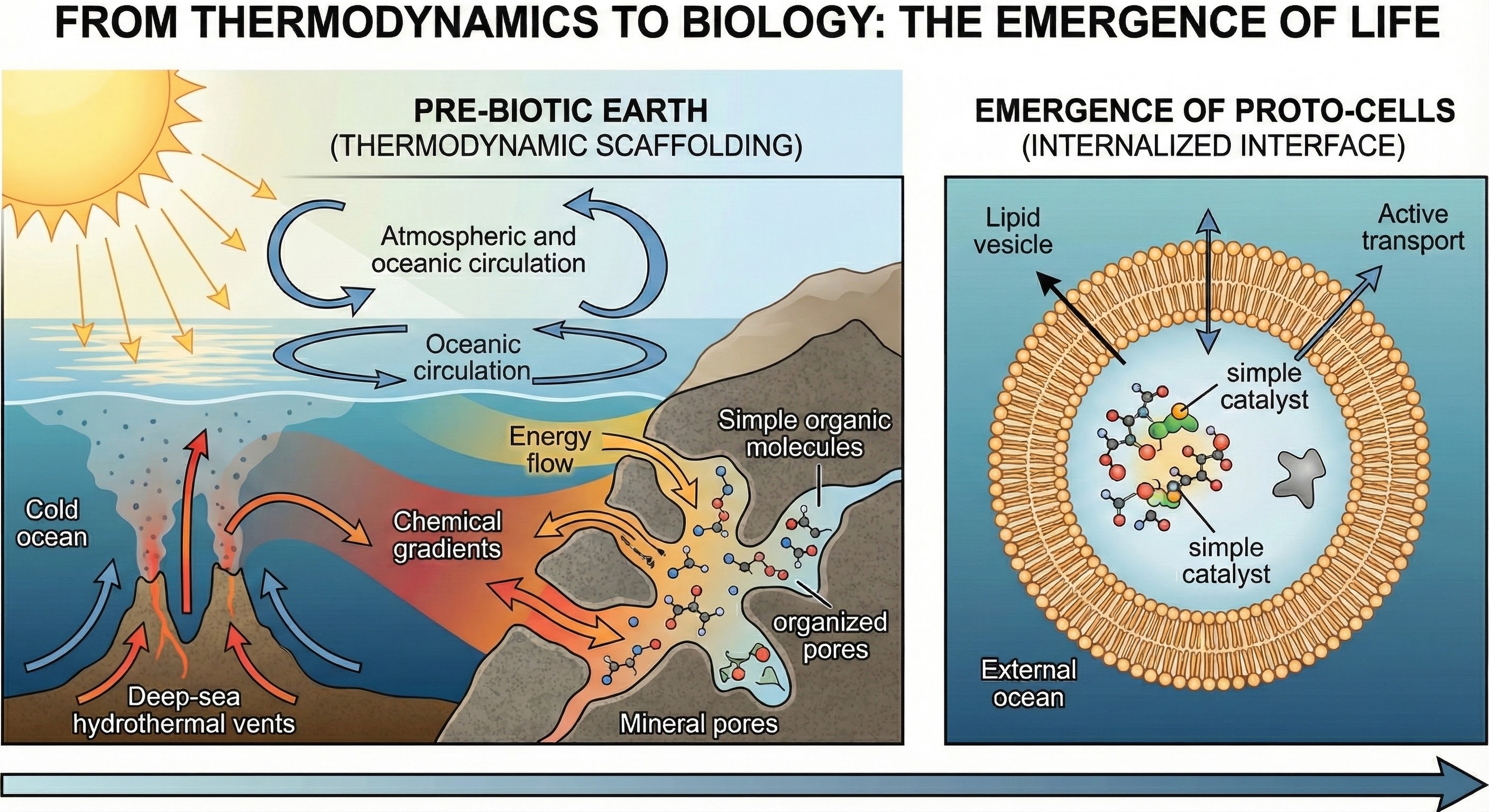

As shown above, the emergence of life from thermodynamic interfaces represents one of the most profound transitions in the universe. This illustration captures the moment when self-maintaining structures first appeared, structures that could actively maintain their boundaries through thermodynamic interfaces. Life didn't emerge despite thermodynamics, but because of it, the ability to manage entropy flow created the possibility for persistent, self-maintaining systems that could evolve and adapt.